Icon of Jonathan Daniels at the Episcopal Divinity School in Boston

I know how much you enjoy my jokes. Let’s dial back the clock to the 1960’s for a joke that isn’t nearly as funny as it is sobering. A nervous northerner headed into the deep south to participate in the Civil Rights Movement prays earnestly to God for safety. After a long pause, a deep but shaky voice from heaven replies, “I will go with you to protect you, but only as far south as Memphis.”

Former U.S. Secretary of State

Condoleezza Rice was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1954. The city then was a stronghold of the Ku Klux

Klan and a community where racism was deeply imbedded in every aspect of

life. In her book, Extraordinary,

Ordinary People: A Memoir of Family, Rice recalled it was “a very

scary place,” and she described how her father had to sit on the front porch of

their home at night with a loaded gun in his lap to keep his family safe. “What I can remember most from this time,”

Rice said, “is the sound of bombs going off in neighborhoods, including our

own.”

In 1965, The Rev. Martin Luther King

urged clergy and concerned citizens from all over our country to join him for a

voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery.

The Rt. Rev. C.C.J. Carpenter, the Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of

Alabama at the time, explicitly told the clergy of our church to stay away, not

because it was too dangerous, but because he felt their presence would stir up

trouble. “This ‘march,’” he said, “is a

foolish business and sad waste of time [reflecting] a childish instinct to

parade at great cost to our state.” Carpenter’s directive was no

small matter because visiting clergy could not visit a diocese without the

bishop’s permission.

On the eve of his

installation as Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in January, 1965, The

Rt. Rev. John Hines stated emphatically that the church “must create an atmosphere in which personal freedom can

prevail.” It is the church’s

responsibility, he said, to make a “forthright stand” against the injustices of

social discrimination. He advocated that

the church should “endorse civil disobedience in situations in which a man’s

conscience tells him that the right thing to do is to disobey civil laws.” Bishop

Hines’ leadership empowered many to “ignore the Carpenter of Alabama in order

to obey the carpenter of Nazareth.” He

was one of some 500 Episcopalians to go to Selma March of 1965.

One of the 500 was Jonathan Myrick

Daniels, a seminarian at the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge,

Massachusetts. Just four years earlier,

the Keene, New Hampshire native was the valedictorian of his graduating class

at the Virginia Military Institute.

He wrote about his experience

travelling to Alabama, citing the hatred he felt directed toward him once

people saw the northern license plates on his car. Even though Daniels was wearing a

seminarian’s collar, one man turned to another and shouted, “Know what he

is?” “No” the friend shouted back. “Why he’s a white niggah.” Sitting at a counter at an all-night truck

stop, Daniels could feel icy stares coming from all directions. At that time, establishments such as this one

had been ordered by federal law to serve all people, regardless of race. Daniels noticed a sign behind the counter:

“ALL CASH RECEIVED FROM SALES TO NIGGERS WILL BE SENT DIRECTLY TO THE UNITED

KLANS OF AMERICA.” Moments later the

server spilled Daniels’ coffee as it was being poured.

As you know, the manner in which the

authorities responded to the march in Selma was brutal and violent. News broadcasts of vicious police dogs, fire

hoses, and tear gas rocked our nation. I

don’t know what Jonathan experienced at that time, but unlike many clergy, he

decided to return to Alabama that summer to assist in a voter-registration

project in Lowndes County. Daniels

explained his decision:

“Something had

happened to me in Selma, which meant I had to come back. I could not stand by in benevolent dispassion

any longer without compromising everything I know and love and value. The imperative was too clear, the stakes too

high, my own identity was called too nakedly into question... I had been blinded by what I saw here (and

elsewhere), and the road to Damascus led, for me, back here.”

For Daniels, it was something much

deeper and more spiritual than a basic moral obligation. He wrote:

“I began to know

in my bones and sinews that I had been truly baptized into the Lord’s death and

resurrection... with them, the black men and white men, with all life, in him

whose Name is above all names that the races and nations shout... we are

indelibly and unspeakably one.”

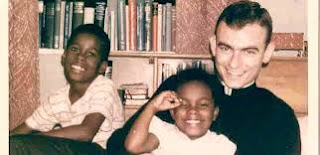

Jonathan Daniels - Summer of 1965

Listen

to a story Daniels told about an experience he had that summer living with an

African-American family:

Bunnie sat astride on my knee. She is four, the youngest of eleven…

children. She smiled, yet there was a

hesitancy in her eyes. Her daddy smiled

down at her and asked, “Do you love Jon?”

Quietly but firmly, Bunnie said, “No.”

We had lived with Bunnie’s family only a few days, and I was sure I knew

what she meant. A part of me seemed to

die inside, and I fought back tears. But

there was nothing I could say, nothing I could do. Wisely, her daddy, who was already a dear

friend, did not pursue the matter… When, a few days later, Bunnie pulled me

down to her, cupped my face with her tiny hands, and kissed me, I knew

something important (and incredibly beautiful) had happened.

Not

everyone warmed up to Daniels being in Alabama, including the parishioners of

the local Episcopal Church. He describes

being interviewed by a local judge in his finally appointed office. Daniels knew that man well because he also

served as the head usher at the church and had refused to allow him to take

communion. He told Jonathan that he and

a fellow seminarian were welcome at the church, “but the nigger trash you bring

with you will never be accepted in [the parish].” Daniels bristled at the thought of these

wonderful people, and especially their children, being referred to as

“trash”. “Our Episcopal Church is a

white church,” the judge continued. He

asserted that Daniels should not be living with an African-American family

“since God made white men and black men separate and if He’d wanted them

comingled He’d have made them all alike.”

At the conclusion of the conversation the judge declared, “I am not

guilty of anything. Only guilty men have

trouble sleeping at night. I don’t have

any trouble sleeping.”

On August 14, 1965

Daniels was part of a demonstration and was arrested along with other

protesters. They were taken in a garbage

truck to small, poorly equipped jail in Hayneville, Alabama where they endured

six days in a cramped jail that lacked air conditioning and adequate sanitary

facilities. Daniels led the group in hymn singing and

prayers to keep up spirits.

They were released on August 20 in what

appears now to be a set up. While a

member of the group used a phone booth just outside the jail to make calls to

arrange for transportation, Jonathan, a Roman Catholic priest, and two African-American

civil rights workers approached a nearby grocery store to purchase some cold

drinks. A volunteer deputy sheriff

holding a shotgun stood at the door and refused to allow entry. He pointed the gun at Ruby Sales, a

seventeen-year-old African-American, and began to fire. Daniels pushed her out of the way and was

killed instantly. Subsequent blasts

wounded the priest. The deputy went on

to brag to his friends “I just shot two preachers”. Later that fall he was acquitted of charges by

an all-white jury.

While

Daniels’ murder was not widely reported at the time, the matter came before

President Lyndon Johnston when an aide sought to help the Daniels family get

their son’s body back to New Hampshire in time for the funeral. Even after death, civil rights workers were

despised by the communities in which their were slain. Martin Luther King often said “one of the

most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was

performed by Jonathan Daniels.”

The Rev. Jim

Newsom, also a VMI graduate, served as St. Paul’s rector during those

tumultuous years. Throughout his

ministry here he was a strong advocate for civil rights and labored in our

community to build bridges across the racial divide. A Virginian

Pilot newspaper article dated February 9, 1967 carried the headline “White

Church Invites Negroes.” St. Paul’s was

hosting a community service for the World Day of Prayer and Jim is quoted as

saying, “In accordance with the purpose of the World Day of Prayer, there will

be no barriers of race, denomination or culture, when church people around the

world come together for prayer.” This

was no small step in our community. The

article mentions by name several prominent white downtown churches that planned

their own alternative service rather than pray with people of color.

In the November,

1967 Vestry minutes, it is recorded that Rev. Newsom announced a community

Thanksgiving Service was going to be held at East End Baptist Church. The minutes report “A general discussion

followed”, but provides no details of the substance. Sarah Newsom remembers St. Paul’s hosted a

Thanksgiving Service here where so many people attended “they were packed to

the rafters.” Knowing that the memory of

an old rector’s wife can be faulty, I searched through the ancient parish

registries to see what I could find. I

learned that in attendance at a service on Thanksgiving in 1968 were the

following ministers:

Donald Dunlap – West End Baptist

A. Elliott – St.

Mark’s Episcopal

D.W. Lamb – Metropolitan Baptist

C.L. Landrum – Suffolk Presbyterian

Jim Newsom – St. Paul’s Episcopal

C.J. Word (who was the preacher for the

service) – East End Baptist

And what about the

attendance? According to the registry,

380 people were in the congregation – score one for the “faulty memory” of the

rector’s wife.

Rev. Newsom, Rev. Dunlap, and Rev. Word

These are just a few

of the examples of Jim’s leadership around civil rights issues in our

community. It is hard to gauge the

lasting impact of his work, but when I returned from twelve days at General

Convention earlier this summer, I had waiting for me a flurry of e-mails from a

bi-racial committee planning a community prayer service after the Charleston

church shooting. This group thought it

to be important that the “minister of St. Paul’s participate and have a place

on the program.” I attribute this to a

deep and abiding memory of our parish’s stance under Jim’s leadership.

The 1991 General

Convention of the Episcopal Church recognized Jonathan Daniels to be a saint

and martyr of our church, setting aside August 14th of each year to

commemorate his acts and witness. Along

with Martin Luther King, he is the only other American enshrined at Canterbury

Cathedral’s chapel of contemporary martyrs.

VMI has established a Jonathan Daniels Humanitarian Award to honor his

memory. Recipients include former

president Jimmy Carter and Representative John Lewis, who was on the Selma

Bridge in 1965.

VMI organizes regular

pilgrimages to Hayneville and 300 people participated in 2013. Upon reading about today’s service in the Suffolk News-Herald, Robert Stephens

posted this comment:

THANK

YOU for sharing this announcement with the local Suffolk community. My son (Fletcher--VMI Cadet) and I will be

traveling to Montgomery, AL this weekend to participate in the Jonathan

Daniels’ Pilgrimage, where the VMIAA is also hosting a reception in his

honor. This unsung Hero deserves much

recognition for being a catalyst and change agent who died for Blacks’ basic and

fundamental right to vote... hence, the Voting Rights Act of 1965!

Ruby Sales was so traumatized by the

experience that she could not speak for seven months after the murder. Eventually she graduated from the same

seminary Daniels attended. She dedicated

her life to be a human rights advocate and founded

The SpiritHouse Project, a non-profit organization and inner-city mission

dedicated to person who saved her life on a blazing hot August day in Alabama.

So here we are, fifty years after

Daniels’ courageous act. It is an

appropriate time to reflect on what has changed over the years and what still

remains to be done. I charge each of you

with the task of doing this work in the coming weeks and months. Let me say concisely that the challenge back

then was to recognize, affirm, and value the basic humanity of every

person. Today’s challenge, it seems to

me, is to recognize, affirm, and value the experience of every person. It is hard to hear about racial discrimination

in our day because the inescapable message from it is that we still have a

long, long way to go if we are going to be the country which our founders

envisioned – a people equal under the law endowed with rights to life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness. My sense

is that Suffolk’s clergy and faith communities are hungry to build more bridges

across the racial divide and to strengthen our bonds of affection for one

another. The time is right for us to

act.

I think what I will take away most from

this commemoration is something Jonathan said in his valedictorian address to

the VMI graduating class of 1961. There

are four arches that lead to the barracks on VMI’s campus. One of the four honors Daniels. Inscribed on the arch are these words from

his address:

“I wish you the decency and nobility of which

you are capable.”

This is an incredible charge for the

outstanding young men and women who train at the fine facility! And it is a great challenge and vision for

each one of us as we seek to be faithful disciples of our Lord and Savior Jesus

Christ, who loved all without partiality or preference.

“I wish you the

decency and nobility of which you are capable.”

I knew of Jonathan’s heroism, but I come

away from this day impressed by his decency and nobility. He sought first, foremost, and always to meet

hatred, brokenness, and injustice with Christ-like love and compassion. That his first instinct in the face of mortal

danger was to protect another by placing himself at risk was laudable, but

probably something many other VMI grads – along with some of the rest of us –

might have done. It was his commitment

to return to the south and the manner in which he carried himself while there

that accounts for why we remember him today.

May the life and witness of Jonathan

Daniels continue to speak to us and to inspire generations to come until our

society perfectly reflects the values of the Kingdom of God.