John 21:1-19

Easter 3 / Year C

Christianity stands alone among the world’s major religions

for the way in which its sacred texts honestly portray the flaws of its major

characters. It begins with Adam, who

manages to mess up paradise. Then there

is Cain, who murders his brother. Joseph

dreams of being superior to his siblings and they, in turn, sell him off to a

passing caravan. Moses commits

manslaughter. Aaron rallies the people

to make a golden idol. David enters into

an adulterous relationship with a neighbor and then arrangers to have her

husband killed in battle. I could go on,

but you get the idea. And this is just

the Old Testament.

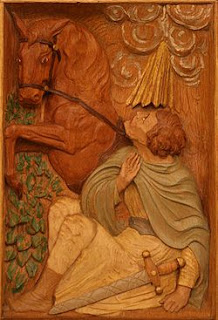

Today’s readings highlight the foibles of two of the most

prominent figures in the New Testament: Peter and Paul. Three times Jesus inquires of Peter, “Do you

love me?” – a not so subtle reminder of the three times the Apostle denies

knowing Jesus. And after eight chapters

focusing on the life of the early Church, the Book of Acts finally gets around

to introducing us to its lead character – Saul of Tarsus. And how do we meet him? By finding out he participates in the stoning

of Stephen, the first Christian martyr, and by vigorously persecuting those who

are known to be a part of “The Way” of Jesus.

And it is not as if these flaws are incidental to each

Apostle’s character. The Scriptures

present them unvarnished in order that readers will know their heroes, warts

and all. Following Peter through the

gospels is something akin to riding a rollercoaster. There are some highs and a lot of lows:

stepping out of the boat and sinking, refuting Jesus’ teaching about how he

must die (to which Jesus responds, “Get behind me, Satan”), lashing out in

violence as Jesus is arrested, and the three denials. Paul, for his part, refers often in his

writings and in his testimony to his past life as a persecutor of the faith.

Why do you think the bible presents its leading figures in such

an honest and unflattering manner by constantly bringing up the past? And what does it mean for us as we (like

them) seek to be faithful followers of Christ?

They say anxiety has to do with fear of the future; fretting

about all the things you can’t imagine or control. Depression, on the other hand, is rooted in

the past. It is dwelling on (maybe even

obsessing about) mistakes and what ifs; what we rue and what we regret. And the more you live with this, the more you

begin to think of yourself as the mistake you made. You become a prisoner of your past.

An opposite approach is equally possible. It involves a recasting of the past in a way

which is not faithful to what actually happened. The other day I read a rather interesting

(but dense) review of a book by David Rieff titled In Praise of Forgetting:

Historical Memories and Its Ironies.

He argues over time cultural memories of triumphs and defeats, things we

got right and things we got wrong, pains we inflicted and pains we endured, “inevitably

fade into caricature or cliché as time passes.”

I’ll spare you the details of his thinking. Interestingly, as our country struggles with how

to make sense of and tell the stories of our past, Rieff believes our failure

to remember “what really happened” is both inevitable and positive.

In Peter and Paul we find two people who neither are

prisoners of their past mistakes nor have succumbed to the temptation of rewriting

the histories of what they have done wrong.

They remind us no one is perfect, which is neither a controversial nor

enlightening insight in and of itself. But

they add to it none of is defined by our actions.

You may tell a lie, but this does not make you a liar in God’s

eyes. You may rob a bank, but God does

not see you as a bank robber. You may have

an addiction, but God does not see you as being an addict. Our actions don’t define us because God

already has told us who we are. We are beloved

children of the Holy One, dear and precious beyond imagining to the One who

created us. It is a self-definition we

embrace at every baptism. It means… God

sees you as a beloved child who told a lie, as a beloved child who robbed a bank,

or as a beloved child who suffers from an addiction. Nothing you do ever will change the beloved

part of who you are. Nothing.

Peter denies Jesus three times, but he is still beloved. Jesus redeems him and commissions him for leadership

in the church. Paul murders and persecutes

God’s faithful followers, but he is still beloved. Jesus appears to him and calls him to a new

and more noble purpose. Each is an example

of what Oscar Wilde once quipped: “Every saint has a past and every sinner has

a future!” By owning up to their faults,

Peter and Paul point us toward God’s grace.

Each reminds us if Jesus can use them, given all they did wrong, than

Jesus can use us too! We do not just

have a past. We have a present and we

have a future.

How do you live in the present with the memories and

consequences of your past? Well, Peter

and Paul tell us we do so not by moving forward either by punishing ourselves or

be excusing ourselves, but by living into God’s unfailing love for us, by building

the foundation of our lives on God’s unfathomable grace, and by embracing the

fact we are God’s beloved child.